Check out my previous essay on Good vs Bad Debt.

We seem to be in the age of debt.

U.S. national debt is at its highest level in history, $36.22 trillion, and rising fast. American household debt is at an all-time high of $18.04 trillion, with credit card balances alone at a record-high of $1.21 trillion. That’s trillion with a T—twelve zeros. And it’s now easier than ever to borrow money and add to that debt.

Financing was once an uncommon practice primarily used for larger assets such as homes, business equipment, and car loans. These loans often required substantial collateral, a longer credit history, and a strong financial standing, further shrinking the pool of qualified applicants.

Nowadays, it’s much easier to access financing for various purchases. We have far more lending options, improved technology for faster approvals, and evolving economic and social norms where consumer credit has become a more integrated part of everyday life. To highlight the credit transformation, any adult can use a service today called buy now, pay later, which enables you to finance less expensive and non-essential goods such as electronics, furniture, and even a DoorDash meal. No credit or collateral required.

However, debt in itself is not bad. It may seem scary because it means that you owe someone. But if used correctly, it can actually be a powerful, beneficial tool. So, how can we use debt to our advantage?

To put it succinctly, debt should never be used for perishables, should mostly be avoided for depreciating assets, and should often be used for appreciating assets, revenue-generating assets, or investments. When it comes to the purchase price, the smaller the price, the less you should use debt, and the higher the price, the more you should consider it.

Let me give you some real-world examples as to exactly why this formula is financially advantageous.

My Car Purchase

Two years ago, I purchased a car for $14,500. I had two options: finance or pay cash. Based on our succinct formula above, a car is a depreciating asset, so the initial reaction is to avoid debt. However, the formula also takes into account the purchase price. And 14 grand is a decent chunk. So that prompted me to explore loan options and compare them to paying cash.

After exploring a few different loans, I chose the following terms from my local credit union: $4,000 down payment, $10,500 financed at 8.74% interest rate. They initially offered a 36-month term at a lower $362.23 monthly payment, but I negotiated to pay more per month for a shorter term to pay less in interest over the life of the loan. Had I taken the lower monthly payment, I would’ve paid a bit over $500 more in lifetime interest in exchange for an extra year.

The total cost of my loan was $2,004 in interest + $940 in loan processing = $2,944 to borrow the money for two years.

Side note: Borrowing money always comes at a cost because of what’s known as the Time Value of Money (TVM). It’s the idea that $1 today is worth more than $1 tomorrow because money today can be invested to earn potentially higher returns or simply used at this moment. Also, due to inflation, the purchasing power is higher today than tomorrow. So, for reasons of risk, inflation, and deferred use of their money, lenders always charge interest to lend it to you. Since a dollar today has the potential to grow into more than a dollar tomorrow, receiving money later has a lower value in today’s terms, justifying an interest charge. If all that sounds convoluted, simply remember that $1 today is always worth more than $1 tomorrow.

Since my car is a depreciating asset and I wasn’t using it to generate revenue, borrowing money only made financial sense if I could invest the $10,500 I would’ve paid cash to earn at least $2,944 in returns.

Keep in mind that I am paying $521 per month towards the loan. So my principle of $10,500 to invest decreases by $521 each month. Another consideration is that although I get to keep $10,500 by financing the car, that is not all of my investment capital.

For the sake of this essay, let’s say I already have $50,000 in my portfolio. Now with the loan, my portfolio can be at $60,500. This is key because it takes a smaller percentage of a large number to yield the same gain as a larger percentage of a smaller number.

If I invested just the loan cash of $10,500, I would need to earn a 28% return in 2 years or 14% per year to earn my loan cost of $2,944.

But with my now larger portfolio of $60,500, I only need a 4.87% gain in 2 years or 2.44% per year to earn my loan cost of $2,944.

If we take into account the withdrawals of $521 each month, the required gain from the $60,500 in invested capital to pay off the loan will be roughly 25.53% over 2 years or 12.77% per year.

As planned, I was able to comfortably pay off my loan using investment profits and actually profit by borrowing the money rather than paying for my car in cash. Had the interest rate been lower or had I managed to yield higher investment returns, the more profitable my financing decision would have been.

House Mortgage

As of 2022, almost 40% of US homeowners own their homes outright (no mortgage). Of the outstanding mortgages, 22% have an interest rate below 3%, and 36% have an interest rate below 4%.

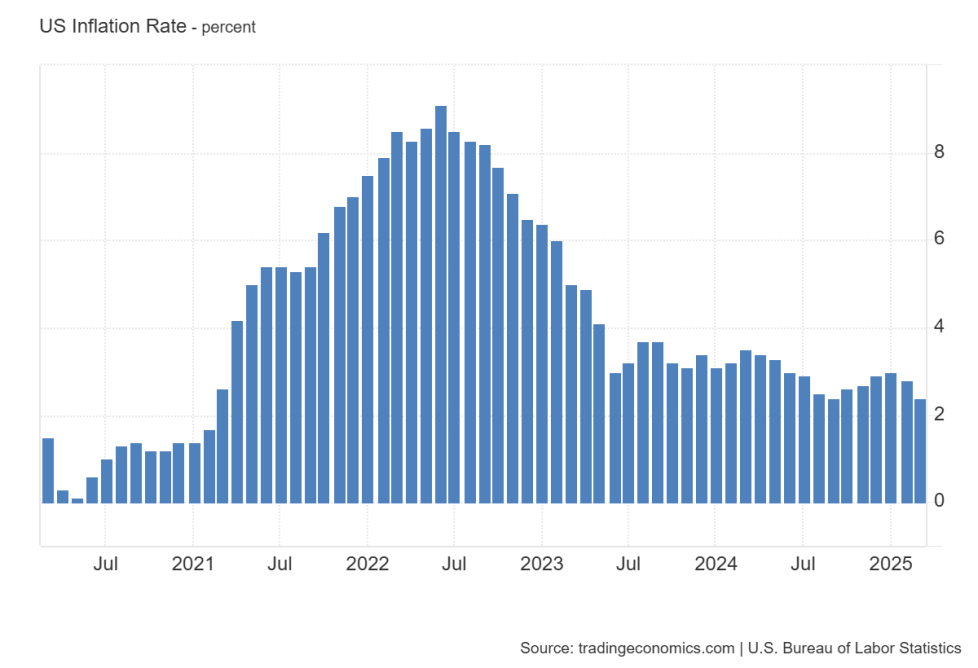

As you may know, we’ve also experienced a few years of relatively high inflation, peaking at 9.1% in June 2022. With all those sub-4% fixed interest rates, an interesting thing happens when your interest rate on a loan is lower than the current rate of inflation.

Inflation means that prices are going up. Prices of goods, housing, wages, etc. As prices go up, the purchasing power of $1 goes down because it takes more to buy the same amount. If purchasing power goes down and thus currency devalues, that means the value of outstanding loans also goes down.

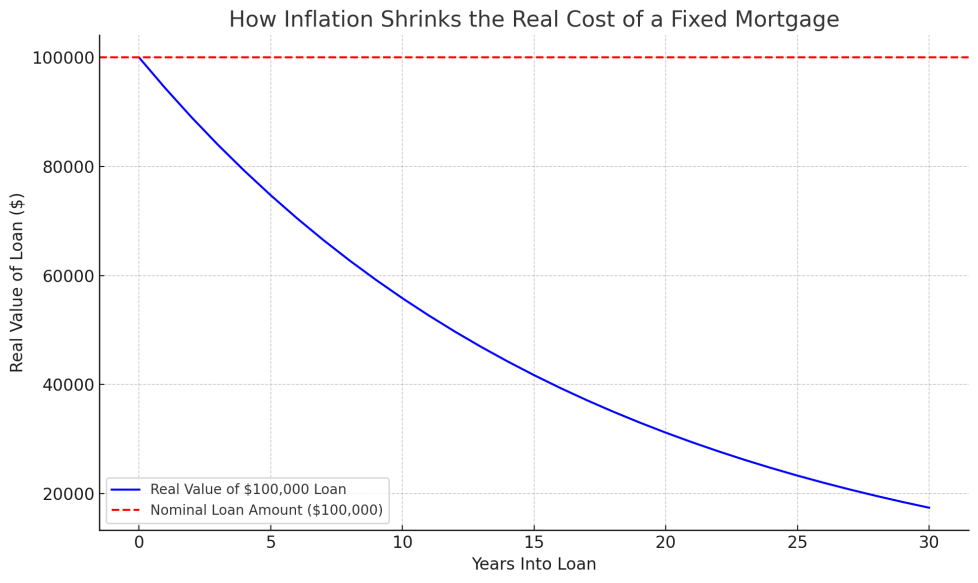

Below is an example of a $100,000 mortgage over 30 years. The red dashed line shows how the $100k stays the same in nominal dollars. The blue line shows how inflation at 6% per year shrinks the real (inflation-adjusted) value of that $100k over time.

After just about 12 years, the real value of your loan is cut by half! By the 30th year, it’s worth only about $17,000 in current-day dollars.

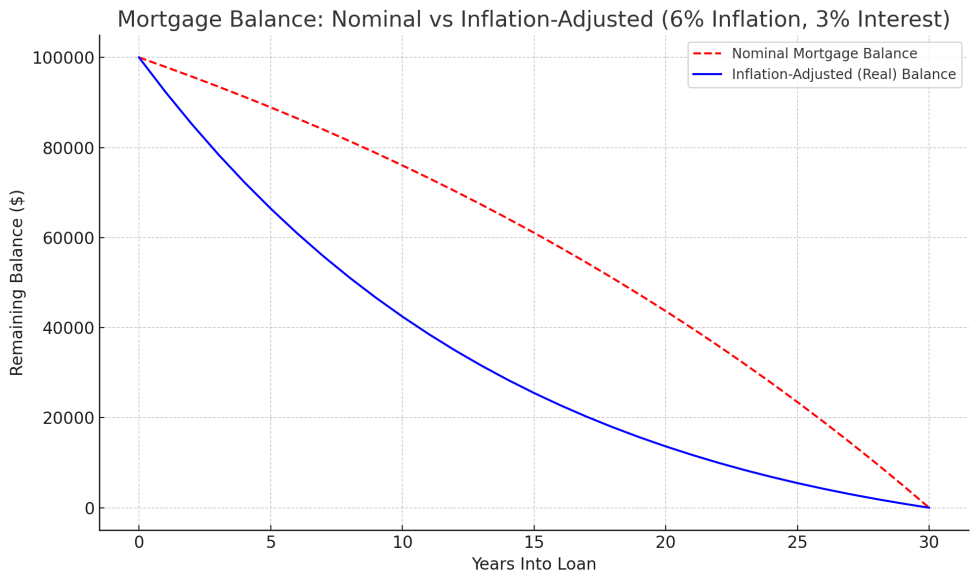

Below is the same scenario, but with mortgage amortization, 6% annual inflation, and a 3% fixed interest rate.

The red dashed line shows your nominal mortgage balance steadily decreasing as you make monthly payments. The blue line shows the real (inflation-adjusted) balance, or how much your debt is worth in today’s dollars over time.

Even though you’re gradually paying the loan off, inflation reduces the burden of that real cost with time. By year 20, your remaining mortgage feels massively ‘cheaper’ than it would have if you started at a higher interest rate or experienced no inflation. You’re essentially paying with ‘cheaper’ money each year.

The benefits of mortgaging a house rather than paying cash, even if you can afford it, are similar (and even stronger than) the reasons I financed my car. The main difference is that it’s an appreciating asset, very expensive, and has tax benefits of using a mortgage. Since 30 years is quite a long time, inflation helps you by increasing the value of your home and decreasing the real value of your loan. You’ll also have the cash in hand to invest or use.

The caveat of financing is that it’s easy to use that extra cash to spend on other liabilities, further increasing your debt in a bad way. Remember, borrowing money comes at a cost. If you’re not paying that cost intelligently, then you’re simply spending your future money.