Disclaimer: I don’t fly private and am not an industry expert. All info below is research based on public information.

If you’re an aviation nerd like me, you spend hours checking FlightRadar24 to see what planes are flying overhead. You might also check where they’re flying from and where they’re going. What airline or charter company is operating, and what make and model of aircraft.

On any given day, more than 87,000 flights traverse the skies over the United States alone, and 5,000 are in the sky at any given moment. Only one-third are commercial carriers like Delta, United, or Southwest. Of all this traffic, air traffic controllers handle 27,178 general aviation flights daily on average (private planes).

Private planes vary massively from a $70,000, $60/hr 2-seater Cessna 150, to a $100+ million, $14,000/hr 45-seater jet. The cost of flying entails much more than just the purchase price of the aircraft. In fact, arguably, the purchase price is the easy part. Other aircraft ownership costs include crew, catering, airport fees, hangar, navigation fees, maintenance, fuel, insurance, and depreciation, to name a few. These costs can sometimes accrue to over 50% of the purchase price per year.

For the large number of business jets in the sky, I’ve always wondered, who are these mysterious people who can afford to pay the average American’s annual salary on one private jet flight? It takes a lot of money and also a pretty significant reason to regularly fly business jets.

I’ve heard individuals worth between $10 to $50 million saying they can’t justify the price of flying private, and sometimes not even first class on commercial airlines. So, who flies private?

It’s a small group of people, as you might expect. However, perhaps not as unusual as you might think.

Stats

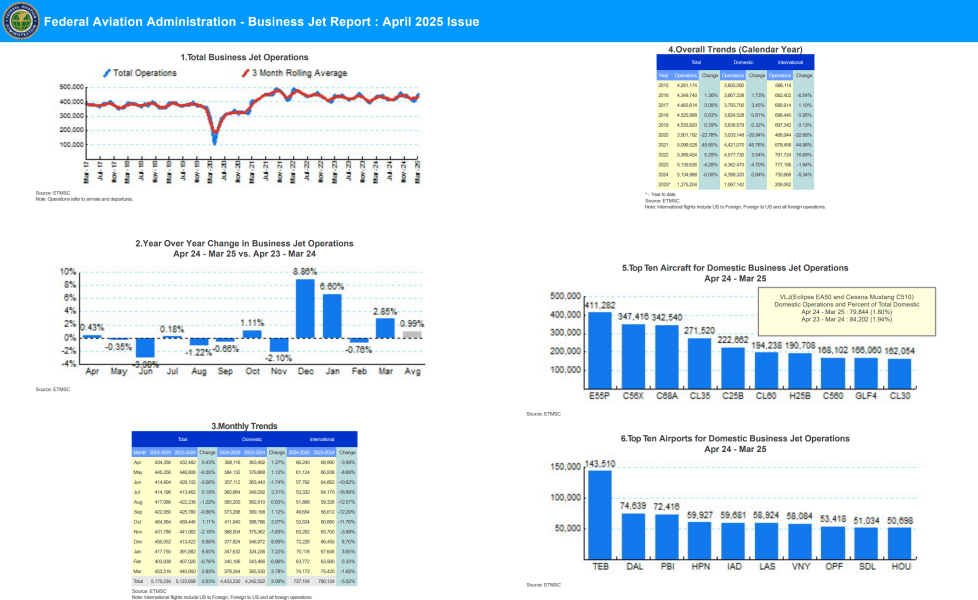

According to the FAA, there were 4,399,320 domestic business jet flights in 2024 alone. That’s an average of 12,020 private jet flights per day!

Of these flights, the four most commonly used aircraft were:

- Embraer Phenom 300. Comfortably seats six, range of 2,000 nm. The purchase price today is around $7,400,000. The Total Annual Budget is an estimated $1,100,264, flying 400 hours/year.

- Cessna Citation Excel. Comfortably seats six to eight, range of 1,858 nm. The purchase price today is around $3,650,000. The Total Annual Budget is an estimated $1,544,800, flying 400 hours/year.

- Cessna Citation Latitude. Comfortably seats seven, range of 2,700 nm. The purchase price today is around $15,000,000. The Total Annual Budget is an estimated $2,200,000, flying 400 hours/year.

- Bombardier Challenger 350. Comfortably seats eight, range of 3,200 nm. The purchase price today is around $17,900,000. The Total Annual Budget is an estimated $1,949,610, flying 400 hours/year.

You can see the current prices of used jets here!

Interestingly, the three most common airports these planes flew into and out of in 2024 were:

- Teterboro Airport (TEB) is by far the most popular airport due to its close proximity to New York City’s business, financial, and entertainment centers. The airport has no commercial traffic and is optimized for private traffic.

- Dallas Love Field (DAL) is much closer to the central business district, entertainment venues, and other important locations compared to the much larger Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport. It’s also less congested and caters more to private flight traffic. Though not as affluent as Manhattan, Dallas is another major economic center in the United States, with a large number of corporations and high-net-worth individuals.

- Palm Beach International Airport (PBI) is located in the heart of Palm Beach County, which encompasses some of the wealthiest communities in the United States, including Palm Beach Island, West Palm Beach, Jupiter, and Wellington. These areas are home to numerous high-net-worth individuals, business executives, and seasonal residents who frequently utilize private aviation. It’s also less congested compared to nearby major commercial hubs, and has a U.S. Customs and Immigration port of entry, facilitating international arrivals and departures for private jets, particularly to and from the Caribbean and Latin America.

Demographic

Private aviation is growing

around the world. But not

everyone who flies privately on

a regular basis owns a plane

As I mentioned earlier, aircraft ownership costs are massive. So it only makes sense to own a jet if you fly very regularly. Although other factors are also important to consider, flying 200+ hours per year is a general threshold where ownership starts to become financially justifiable. Some sources push this higher, towards 200-400 hours per year, especially for light jets. For larger, more expensive jets, the threshold for ownership is even higher due to the greater fixed costs.

VistaJet, one of the leading global jet charter companies, has seen a trend away from ownership, as flying without owning becomes easier and more convenient. On-demand chartering, membership programs (jetcards), and fractional ownership have become more popular and often more affordable ways to fly private.

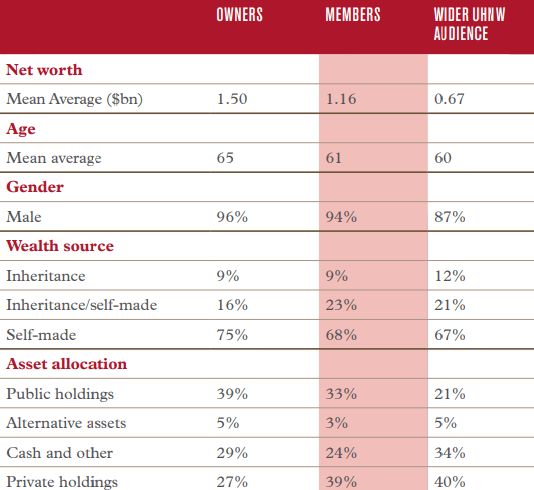

Today’s business jet fliers can be classified into three categories: Owners, members, and the wider ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) audience.

Some of the ultra-wealthy use more than one way of flying, depending on their needs. However, each group displays a number of distinctive traits, whether related to age, geography, wealth source, asset holdings, or average net worth.

I knew business jet ownership was hugely expensive, but was surprised to find that the average net worth of an owner is $1.5 billion, and 35% of owners are worth over $500 million. Unsurprisingly, they are typically older, male, and married. The majority of owners are over 60 and have created some or all of their wealth themselves; expected as it’s commonly known that most billionaires are considered self-made.

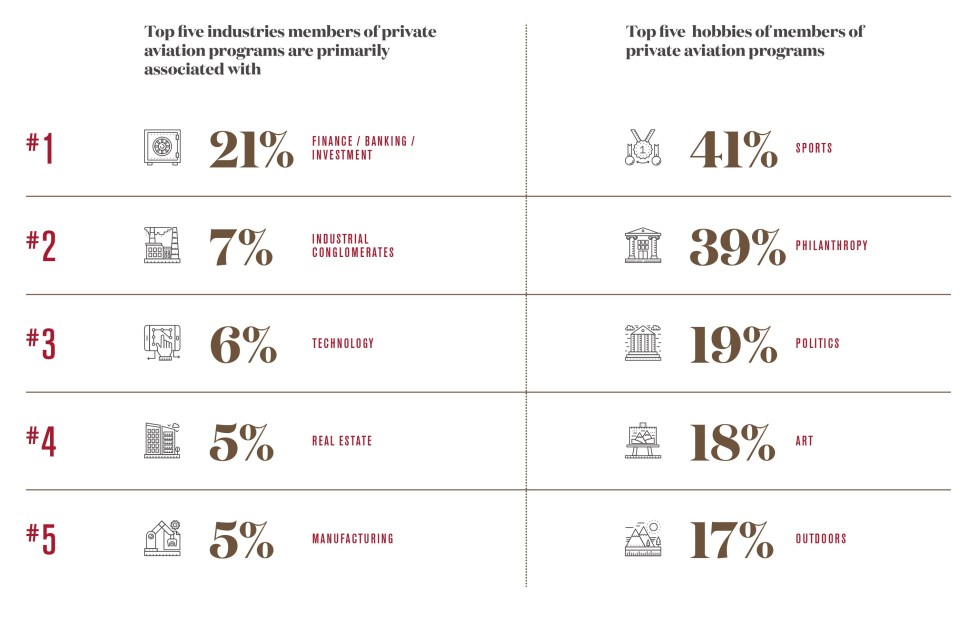

Diving into the wealth of these owners, public holdings make up their largest asset allocation. They typically own a share of the public companies that helped create their wealth, having been an executive or founder. Nearly 20% of them are in the finance, banking, and investment industries, compared with the global average of 14.5%. The large proportion of wealth in public holdings suggests that an increased interest in the stock market and private investment may prompt an increased need to fly privately.

Philanthropy ranks as the most common interest among owners, with nearly half of them engaged in benevolent causes. This is significantly higher than the global UHNW individual average of 36.3%, as philanthropy is typically more predominant at higher wealth levels. Sports rank second on the list, with nearly half showing interest.

The second class of business jet fliers, members, are also significantly wealthier than the typical UHNW, with an average of $1.1 billion, and 28% having more than $500 million in net worth. Membership is more financially and logistically attractive to frequent fliers than on-demand chartering and commercial flights.

Interestingly, over half of owners also use a private flying program because, on many occasions, they can be more efficient than using their own aircraft for certain types of flight. For example, when their plane is down for maintenance, or they require a smaller or larger plane for a specific mission.

Most of these individuals are also self-made, and most of their wealth is in private holdings at 39%. The average member owns a private company and may be using the flight programs in their name, but on behalf of the company.

Finance, banking, and investment are the major business activities, totaling 21% of the group, and is 3x the next biggest industry of industrial conglomerates. Compared with owners, 6% of members are primarily in the tech industry, highlighting the younger customer base for membership. For members, sports beat philanthropy for the most common interest at 41%.

The last group, the wider UHNW population, is, as expected, the youngest and least wealthy of the three. They have an average net worth of ONLY $67 million, highlighting just how expensive ownership and even membership private flying is.

This group charters on-demand flights or uses first or business class on commercial airlines. They’re typically younger and so have had less time to grow their wealth. Interestingly, women make up a higher proportion in this cohort.

This group also has the highest proportion of inheritors, with 12% having inherited all their wealth. Private holdings make up the highest proportion of the average portfolio, although cash and other equivalents are much higher than other groups at 34% (compared to the 24% and 29% held by membership users and owners respectively). Finance is the most common industry, although there has been a diversification in recent years, such as the expansion of tech, growing wealth in emerging markets, and globalization.

Who And Why

Given the array of choices for flying private, each individual must consider their situation as each flight is largely decided on its individual merits. Choosing whether to own or use some form of renting doesn’t just come down to how much money one has. The factors in this decision largely depend on the amount of time spent in the air over a year, the nature of those flights (for example, business or leisure), and the value trade-off.

According to the data, only a few thousand individuals can afford to own a business jet, and only a few thousand more can afford to charter. But this doesn’t represent the entire class of private fliers. Many who occupy a seat on a business jet don’t pay at all. Especially for leisurely travel, family members, friends, and pets often accompany the paying flier. Other commonly cited passengers include security guards, staff, and crew.

VistaJet concluded four key typologies. The first, conventional frequency, mostly flies for business between hub cities like Los Angeles and London. This flier is typically a C-suite or just below within mid-size organizations, or a senior manager within a larger organization. While long-haul is the pattern for their work lives, they’ll often travel short-haul for vacations. Typically worth at least $10 million, these individuals fly first class on commercial and some on-demand private flights for shorter leisure trips.

The second type, complete control, has significantly higher time demands and more sensitivity in their work. Likely a hub traveler, but also more likely to visit other less common destinations. This person travels frequently (over 60 flight hours per month) because of the high-profile nature of their work. As a result, they also have high security needs. This person is typically an owner, whether that’s through himself or through the company (there are tax benefits to owning and using a plane for business), but is likely to also use on-demand chartering for some flights that their jet can’t do due to maintenance or otherwise. This flier is likely to be worth over $750 million.

The third is connected and seamless, as flying is the backbone of their work life, and a substantial part of their leisure life. They’re likely to travel mid-long haul with a wide variety of destinations, both to larger cities and uncommon locations. They usually have a higher requirement for security both on and off board for business and family safety. This flier is typically worth over $100 million, but simply doesn’t have the time, inclination, or funds required to run their own jet, meaning they are often part of a membership program.

The last type is experiential and occasional. They typically take domestic leisure flights and value the experience of travel itself as much as their actual leisure. Friends and family frequently accompany them, and these flights are driven by seasonal trends like skiing season in Geneva. They’re usually worth over $50 million and primarily use on-demand charter services.

Conclusion

One of the most interesting facts I discovered through this research is that an estimated 40% of all business jet flights have no passengers in them at all. The reasoning behind this, as one redditor explained, “It’s pretty much due to the high level customization when it comes to planning your route. Clients book a flight from a very specific location, so it more often than not result in a plane having to be repositioned to the origin airport. In the case of a one-way trip, plane then has to fly back to its base. So in this example, basically out of 3 flights, 2 flew empty.”

Commonly known as empty-leg or repositioning flights, these happen for multiple reasons. These are flights that are ferrying from their base to pick up customers, ferrying back to their base after dropping off customers, repositioning after dropping off customers to wherever the next customers are starting their journeys, and flying to and from maintenance locations. These repositioning flights happen for various reasons, whether the flier is an owner or on-demand, and thus adds up to a surprisingly large portion of the time a private jet spends in the air.

You might be thinking, what a waste! If the plane is empty, can’t someone pay a discount to hitch that flight to wherever it’s going? Guess what, you can! This opens a last category of business jet fliers. Those who value the experience of traveling on a private plane higher than the destination itself or any other part of the leisure. Flying private for the sake of flying private.

Empty-leg flights are highly uncustomizable and are 100% prioritized on the client who booked the main flight. The plane must get to the customer on time, clean, undamaged, and fully prepared. For this reason, so many plane operators and owners would rather leave repositioning flights empty.

However, some companies like Volato offer a $2,000/yr membership that allows you to enter waitlists for empty-leg flights to random destinations. Totally impractical for saving time or traveling efficiently (all the actual reasons to fly private), these services are purely for those who want to experience a private jet flight.

Another interesting insight is that a small percentage of frequent fliers account for a disproportionately large share of total flight hours. Going back to the FAA’s data, there were almost 4.4 million domestic business jet flights in 2024 alone. While there’s no exact number on what percent of fliers accounted for X% of those flights, I can confidently say that it’s highly concentrated for several reasons.

First, the number of business jet owners is relatively small compared to the total number of UHNW. Of the surveyed private fliers, the most frequent passengers fly a significant amount per year. Of these frequent fliers, they tend to routinely fly on established business corridors, as we found in the busiest business jet airports (Teterboro, Dallas, and Palm Beach). Lastly, the rise in membership programs further shows the concentration, since memberships cater to people who fly enough to benefit from more consistent access than on-demand charter, but not enough to justify full ownership.

These programs inherently cater to frequent fliers. Though I can’t give an exact number, it’s likely that the top 10% of business jet fliers account for up to 60% of all the flight hours, and it would be even more if there weren’t so many empty flights!

Yes, flying private is expensive. But what does expensive mean? Objectively, $1 million is a lot of money because there is a lot you can do with that amount. But for it to be expensive means it’s a lot relative to your total.

For the median American net worth of approximately $200,000, spending $1 million per year on flights is crazy expensive and, actually, mathematically not possible. That’s why it sounds expensive to us normal folk. But for a person worth $1 billion, spending $1 million per year on flights is equivalent to the average American spending $200 per year on flights! It’s hard to even find one domestic round-trip flight in economy for $200.

Another note about finances, we discovered that out of all the UHNW individuals, only a small percentage of them own a jet. Even those who have a need to fly and are worth tens or hundreds of millions still can’t afford or justify the cost. Part of this reason comes down to this: there’s a difference between liquid wealth and paper wealth. Someone could be worth $10 million, but $9.9 million of that is tied up in a volatile, illiquid crypto meme coin. This means they can’t easily and likely won’t ever be able to turn that amount into spendable money.

Real estate, the single largest asset class in the world, is considered an illiquid asset. Meaning most of our wealth is tied into this asset that can’t easily be converted into spendable money. It doesn’t mean it’s not valuable. But you can’t spend or trade it quickly.

Also, depending on the nature of the asset, it might be worth an amount on paper, but require years in time to fully liquidate it at that amount. If you wanted to expedite the liquidation process, you’d sacrifice some value. This is a large reason why even some ultra-wealthy individuals still can’t afford the higher tiers of private flying. As they say, ‘cash is king’.

Flying private comes with its perks, but it’s really not necessary for the vast majority of people. Those birds are charming to look at, and sure, it’s glamorous, but in the meantime, I’ll be happy admiring from afar. I guess that’s where the saying comes from, “If it flies, floats or fornicates, always rent it – it’s cheaper in the long run.”

Sources:

https://www.sherpareport.com/aircraft/private-flights-new-highs.html

https://www.vistajet.com/globalassets/documents/jettravelerreport.pdf

https://elite-wings.com/2023-us-business-aviation-market-in-numbers/

https://www.bjtonline.com/business-jet-news/what-santulli-accomplished