Perfection is something that does not exist. It’s more of a concept or an abstraction. Some might say God is the only thing that knows or is perfect. And yet, the goal in racing is to chase perfection.

Nobody can ever achieve it, but we can all try. That is the art of racing.

A race is a competition of who can cross the finish line first. Races usually have rules like no bumping into others, and there are boundaries around the track that you can’t cross.

You can race practically anything that moves. You can have a footrace, using nothing but your body. You can also race man-made machines; bicycles, roller skates, airplanes, trucks, and of course, cars. All forms of racing share the same ultimate goal: to be the fastest around the track. For now, we’ll focus on car racing.

During a lap, there are infinite minuscule variations you can make to the throttle, brake, and steering, which affect the car’s balance, speed, acceleration/deceleration, lateral movement, and grip. It not only matters when you apply these inputs, but also by how much.

The brake and throttle are not on/off switches. They range from 0% to 100%. They’re not always linear either. Maintaining a constant 20% brake pressure will not always give you a constant deceleration. This is because:

1. Downforce is the air pushing the car into the ground, increasing the grip of the tires. Downforce decreases as you slow down. There’s also less air resistance as you slow down. At 60 mph, air resistance is four times greater than at 30 mph. This drag acts as a constantly changing supplementary braking force, helping you to slow down.

2. The engine provides a braking effect, especially at higher RPMs. This is conveniently known as engine braking. When you lift off the throttle, your engine is decelerating the car without the use of the brakes. It works by converting the engine from a power-producing machine into a power-absorbing one. Think of it as the wheels forcing the engine to turn, and the engine’s internal resistance acts as a brake.

3. Tires degradate with use, reducing the grip.

So the brake pedal is not as simple as holding constant pressure to get continuous deceleration. The same goes for the accelerator. Depending on the RPMs, you will experience an unusually low or high amount of power with the same throttle setting. This is due to the powerband. You get less torque and horsepower at lower RPMs. Then it increases with RPMs before dropping off slightly near the redline.

If you’ve ever tried accelerating in a high gear when the engine is quiet and low-pitched, you may have noticed your car won’t accelerate very fast. But when you downshift and apply the same amount of throttle, your engine will scream. You’ll be glued back to your seat as the car thrusts forward until redline.

Another common nuance of the accelerator comes from the turbocharger. If your car has one, you’ll experience a momentary lag in power each time you step on the accelerator. This can complicate the smoothness of power delivery, which is crucial during apex and exits.

The steering wheel is another complex control system on a car. It can be turned to each side by approximately 180 degrees if it’s a formula racecar and 900 degrees (2.5 turns of the wheel) for a typical road car.

Like the brake and throttle, the steering wheel is not as simple as it seems. Your car will not always turn in the direction you point your wheels. Oversteer and understeer occur when you don’t take into account grip, speed, brake, and throttle inputs while you steer.

Understeer is essentially when you turn the steering wheel too much, too quickly, at too high a speed. The front tires lose grip, and instead of turning, the car continues to go straight. Counterintuitively, when you experience understeer, the more you try to turn the wheel, the worse the understeer will get.

Oversteer occurs when the rear tires lose grip. This typically happens by accelerating too much too soon in a corner with a rear-wheel-drive car. It can also happen with a sudden weight shift, like lifting off the throttle mid-corner.

Tires and grip are among the single most important aspects of a car. It doesn’t matter how powerful your engine is. If you can’t stick to the ground, you won’t move around a track very quickly. You can go down a rabbit hole of tires and grip here if you’d like.

If grip is the most important aspect of a car, then managing the weight and balance is arguably the most important skill of a racer, because it directly affects the grip. Setting up the car before going on track can help a lot. Things like lowering the center of gravity by lowering the ride height. Stiffening the suspension, adjusting the camber of the tires, and adjusting tire pressure, etc. But setup can only do so much. The driver must also manage the balance by manipulating the controls.

When you step on the accelerator, the car’s weight shifts to the back of the car. When you brake, it shifts to the front. When you turn right, the car leans left. Turn left, and it leans right. Drive through a compression, and the suspension will contract, and the grip will momentarily increase, then modulate. Drive over a bump, and the car will become light, losing grip momentarily.

Driving uphill, downhill, on a banked corner, over a curb, or over debris all momentarily affect the balance of the car, which affects the grip. There can also be a combination of any of these at the same time. Without skilled adjustment by the driver, valuable lap time will be lost in these areas. Or worse, you could lose control of the car and crash. The best drivers know beforehand exactly how the car behaves in each scenario and adjusts suitably using control inputs. It’s quite amazing, really.

They lift all pedals before a jump, knowing that in less than a second, the car will lose half its grip for a moment. They correct their steering right before going over a curb, knowing the front grip will momentarily decrease from the bump and slippery surface. They know how to manipulate the car to continue, as quickly as possible, through all these areas.

There’s a reason quick reaction time is one of the most important skills for a racer; every millisecond counts. With everything I’ve mentioned so far, you can now imagine the infinite combinations of brake, throttle, and steering inputs across each millisecond of a 90-second lap. Somewhere out there is a flawless consecutive combination that forms the perfect lap.

For someone who doesn’t know much about car racing, they might view it as a monotonous event. Maybe there’s an exciting crash or two. I know I used to view it this way. Just step on the accelerator and steer the car, it’s so simple, right? But if you look at the techniques that separate lap times from a pro racer vs a novice, you see some counterintuitive and strange manipulation of the car using these inputs.

For example, the picture below is turn 3 at Road America in a Lamborghini. It’s an 80-degree sharp right-hand turn. Notice how, for a moment, his steering wheel is pointed pretty far left. Yet, he needs to rotate the car more to the right to stay on course. Why would he do that?

This is because he’s applying throttle on the corner exit to regain speed. He actually applied a bit too much throttle, and the rear axle is slipping out. In a powerful rear-wheel drive car, as you apply more and more throttle, you need to straighten the wheel more and more, or else the tail will spin all the way around. This same phenomenon also applies to the brakes. The more you press on the brake pedal, the straighter you need to keep your wheel to deccelerate without sliding.

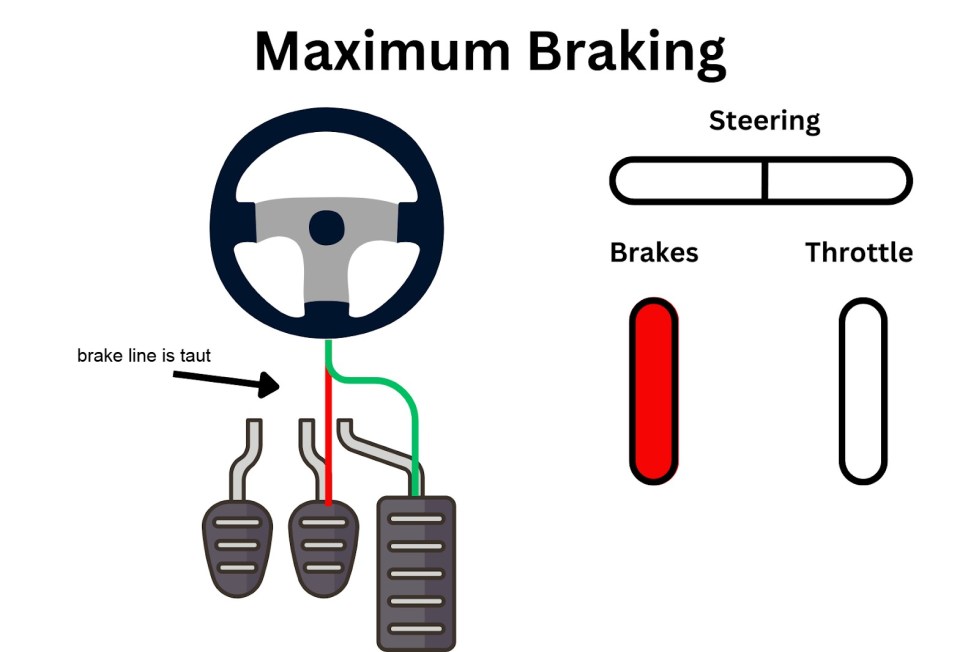

Racing coaches refer to this as string theory.

Under maximum braking or acceleration, one of the strings is taut and will prevent the steering wheel from turning. Under maximum steering, both pedals are pulled upward by the steering wheel and cannot be depressed much, if at all. And so the correct technique for entering a corner with maximal grip is slowly coming off the brakes as you increase your steering. This is called trail braking. The same principle applies to the corner exit. As you straighten the wheel, you’re able to apply more and more throttle without spinning out.

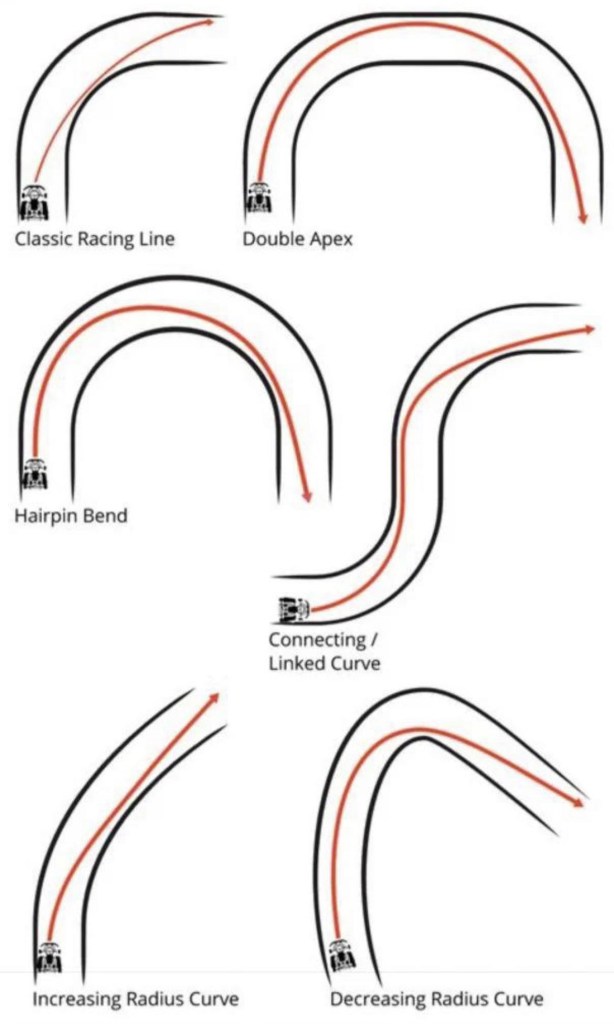

To drive fast, racers also must understand racing lines. The racing line is the quickest way through any corner. It has three stages: turn in, apex, and exit. As simple as it might seem, racing lines change based on many factors. The bank and angle of the corner, the car you’re driving, the condition of the track surface, and the characteristics of the following corner all completely alter the optimal racing line.

For example, in a lower-powered vehicle like a go-kart, the line becomes more curved versus a powerful car that can be sharper. A kart has relatively poor acceleration, so it must maintain as much speed as possible mid-corner. Contrarily, a powerful car can sharpen its line by braking later because it can regain speed quickly on acceleration.

Another example, wet lines, are completely off the standard racing lines. This is because standard lines have a lot of rubber laid down in those areas from other cars. That rubber makes it much more grippy when it’s dry, and much more slippery in the wet. So wet lines are off the normal racing lines.

Finally, the following corner is also a vital factor because your corner entry is just as important as the apex and exit. Some might argue it’s the most important part of a turn. If you have two turns back-to-back, that first turn must set you up for a good entry into the next. That often makes the line into the first corner seem non-standard to set you up for a good entry on the next one.

Telemetry

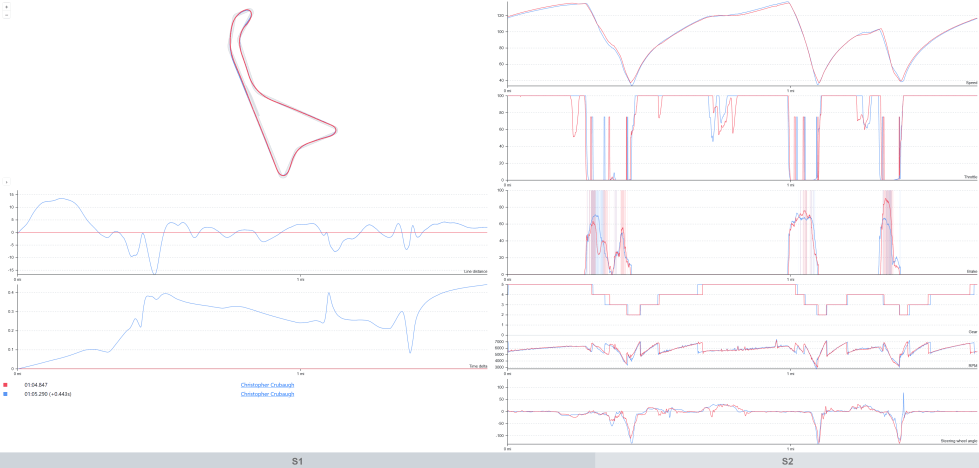

The importance of precision starts to get noticeable when digging into driver telemetry. Below is telemetry data from two of my laps in the racing simulator, iRacing, with the BMW M2 CS at Circuito de Navarra medium layout.

The Red lines (the reference lap) represent my faster lap time of 1:04.847

The Blue lines represent my slower lap time of 1:05:290 (+0.443 seconds slower)

The software lets you analyze driver inputs throughout a lap. You can zoom in on specific moments or sectors to pinpoint areas of improvement.

The top left of the chart shows my racing line through the track. Below that is how far I deviated from the racing line on my reference lap. Below that is the time delta, which is the difference in time between my slow and reference laps. The graphs on the right-hand side show the differences in speed, throttle, and brake inputs. They also show gear changes, RPMs, and my steering over the course of the lap.

First off, one of the cool things about racing is that time is everything. Everyone is fighting to shave every millisecond from their laptime to get as close to perfection as possible. Ideally, they want to do this consistently over many laps. To be 4 tenths slower per lap is a lot. The race I was competing in at this track was about 25 laps total. 4 tenths multiplied by 25 laps is 10 seconds, a lot of time in the racing world.

To give you context of how precious time is in racing, the gap between 1st and 2nd place at this year’s 24 Hours of Le Mans race was 14 seconds! Let me reiterate. After 24 continuous hours, 387 laps, and 3,277 miles, which is far enough to traverse from the United States to Europe, the first and second place only had a 14-second gap between them. That’s an average gain of 0.0362 seconds per lap—not even half of a car’s length.

So we want to shave every millisecond off our time, but we also need to take into account risk. Of course, the largest risk is getting physically hurt. Sometimes, a position is gained or lost based on who is willing to take more risks.

There is an infamous moment in F1 history where Fernando Alonso was approaching Michael Schumaker into Suzuka’s 130R, a high-speed left-hander that follows a long straight. These were two of the best and notoriously aggressive drivers of their time.

As Fernando swept around the outside of Michael, Alonso’s speed at the apex of the corner was 208mph. He knew that any contact between the two cars would have resulted in an accident that at least one of them might not have escaped unhurt. Asked about it a few weeks later, Alonso told the veteran F1 journalist Nigel Roebuck “At times like that, I always remember that Michael has two kids.”

Depending on the racetrack and car, inherent risk increases or decreases. The faster the car, the greater the risk, the slower the less. For tracks, some have massive forgiving runoff areas that allow for some mistakes (see Red Bull Ring and Fuji Speedway). Others have nothing but a concrete wall that will demolish your car if you touch it at speed (Nordschleife and Monaco).

Car parts are expensive, so you also risk financial burden. Motorsports is known as a sport for the wealthy. However, many drivers, especially in lower-tier series, come from modest backgrounds and are funding their drive with a tight budget. These drivers have massive pressure. They must push hard enough to compete for fast lap times, but also can’t afford to make many, if any, mistakes.

Risk tolerance also varies by session. If you’re in a practice session, your risk should be minimal. You don’t win anything for setting a fast time in practice. Risk tolerance increases during qualifying, as you want a good start position for the race. And for most of a race, the risk tolerance drops again because you need to finish to place anything at all. However, your goal as a driver is to maximize the potential of the car you are driving, and risk naturally comes with that.

Back to my telemetry data. From first glance, all my inputs seem fairly similar between my fast and slow laps. By looking at the delta below, I highlighted a moment where the delta steadily goes up quite a bit. The other parts of the chart help me identify that it was during a sweeping right-hand turn into a hairpin. The telemetry shows that my mistake came from braking later and much harder, but then I ended up overslowing by a considerable amount into the hairpin. I was then late on the throttle, completely messing up the exit before a long straight. This lost me almost 3 tenths before regaining a bit of time back in the middle sector.

The highlighted section below was probably my largest mistake. This is the final turn right before the long straight. Those exits are extremely important because any speed gained is then carried down the entire length of the straight. Conversely, a bad exit with slow speed multiplies over the length of the straight, substantially harming your lap time.

My mistake during the last corner was a combination of things. The racing line shows I didn’t stabilize myself well before braking. I might’ve even braked on the outside curb, where there’s less grip, so I couldn’t slow the car down well. Then I turned in much sooner than my quick reference lap. Since I carried too much speed into the corner, I was late on the throttle, which screwed up my exit.

The steering data shows a massive correction during the exit, indicating I was applying too much throttle too soon while trying to turn. So I messed up the entry and exit and compromised that crucial corner, losing almost 2.5 tenths from that corner alone. My inputs didn’t vary massively between the two laps, but it resulted in a very different lap.

It’s In The Details

Racing is all about precision and being able to repeat the correct inputs at the same exact points each lap until the track or car conditions change. Then you must adjust accordingly on the fly. This explains how racers can drive within inches of each other at high speeds under braking and through corners. Everyone is mostly doing the same thing, only with small variations, so they’re fairly predictable.

It’s also important to mention that the difficulty of fast lap times multiplies when you’re driving wheel-to-wheel. A driver could be quick at solo hot laps, but it’s a whole different ball game racing beside others who desperately want to get ahead of you.

Racecraft is an entirely different skill to master. There’s overtaking, defending, letting others safely pass, and driving different racing lines. You also need good spatial awareness and prediction skills to get as close as you can to others and to the edge of the track limits without crashing.

Racing is most comparable to golf. The two may not be the most physical sports. Though they are, in fact, physically demanding. Yet, more importantly is the skill of precision and remaining calm and focused under pressure.

In golf, you have a lot of time to think. You have spectators nearby, judging and heckling. If you’re having a bad game or become intimidated by your opponent, you can easily crumble for the rest of the tournament. If you’re thinking about what you’re going to eat for dinner during your swing, you’ll shunt it and fall behind.

Golf is a game where you need to swing different metal clubs, depending on the distance, to hit a tiny ball hundreds of yards into a tiny hole in as few strokes as possible. Every aspect of a golf swing is a matter of millimeters and degrees. A clubface that is off by just one or two degrees at impact can send a ball tens of yards off target on a long drive.

A slight misread of the green or an uncalibrated stroke on a putt can be the difference between sinking a birdie and getting a par. This micro-level precision is what makes the sport so challenging. You can make a seemingly perfect swing, but a tiny flaw in your setup, grip, or ball-striking can result in a wildly different outcome. And it doesn’t matter how well you can shoot one shot. A hole-in-one won’t win you a round of golf. To be good, you must swing well consistently.

As legendary golfer Jack Nicklaus famously said, “Golf is 90% mental.” You have no teammate to rely on. You have to manage infinite unpredictable factors like rain, wind, and ball bounce. There’s intense concentration for hours. You must be in a state of flow and rhythm that mustn’t be broken until the end of the game.

This is almost identical to racing. You are the only one piloting the racecar. You’re dealing with the stress of all the aforementioned risks and the hecklers. You must be in flow, in rhythm, and nail each consecutive corner, each swing. It’s a game of micro inputs, millimeters. Get discouraged, and you’ll start questioning your ability and tumble down the leaderboards in a heartbeat. You feel ecstatic when you’re playing good, and you never wanna play again when you’re performing poorly.

One of my main sports growing up was basketball. My playing style relied on athleticism and intense effort. As a smaller point guard in high school, it didn’t matter how big the defender was. I’d always charge at full speed and attempt to outjump whoever was in front of me for a hard-fought layup. The more desperate I was for points, the more intensity I’d play with. Just try harder, dig deeper.

In hindsight, I could’ve played much better had I used finesse. Pull up for a jump shot once in a while, keep them guessing. I tired myself out by constantly sprinting and jumping when I could’ve played better with less effort and more finesse.

This same effortless finesse applies to racing. More so than basketball, I’d say. When someone is quicker than me on the racetrack, my instinct is to just try harder. Tense my muscles, fight the car more, brake later, turn the wheel harder and faster, slam the brake and throttle quicker. This actually makes me slower. Much slower and more reckless. There’s a saying in racing, “slow is smooth and smooth is fast.”

A fast lap is about finesse, not intensity. Precision, not force. And you must remain calm. I heard a racing coach once say he can predict whether a lap will be fast or not based on the heart rate of the driver. Despite the screaming engines, the fear of making a mistake, the crowd, and all other pressures, you must remain very calm to perform well.

For me, it’s frustrating because you can’t just try harder. To improve, you have to go back and work on technique. Study the track and your telemetry data, practice trail braking, practice race craft, practice entry, apex, and exits. Practice, practice, practice.

As of today, every single one of the best racers in the world has all started at a very young age. This is because there are no shortcuts to perfecting the craft. In the same way that the best musicians began young, it takes time to refine technique.

Watch an onboard of Max Verstappen and you’ll see how silky smooth he is on steering, brakes, and throttle. He’s as calm as if he were sitting on his couch in his living room. His turn-in is smooth, his braking and throttle pressure are gradual and patient. It almost seems like he’s driving slowly, but his laptimes are unbeatable. He makes it look so easy. But he’s doing things to that car that most of us can’t even comprehend.

The Art

I deliberately titled this paper The Art of Racing for a reason. Racing is an art. You have man and you have machine. The machine is an engineering marvel in its own right. The aerodynamics manipulating the airflow, the engine combusting over 140 times per second at idle, the brakes slowing a 2700lbs car in a heartbeat, and the tires gripping the car around corners like it’s on rails.

And of course, there’s the human.

Why do humans even race cars? AI bots have already proven to be better racecar drivers than humans, at least on the simulator. They’re computers, so they have near-flawless racecraft with no mistakes. A feat no human could ever match. So the natural question is, will AI bot racing ever overtake human racing? Absolutely not!

One reason is due to competition. Racing is an extremely challenging, unforgiving, and rewarding form of competition. It’s a game of balancing risk and reward, emotions, strategy, and technique. We humans not only want to win, but we want to win against worthy opponents who push us to our limits.

The art of racing is the pursuit of perfection. It’s theoretically there, but can never be attained. However, we can all strive for it. The thrill of the pursuit, mastering the technique of piloting the beastly machine, and the composure to overcome any emotional impulses. The art is the imperfection and infinite possibilities.