This is a continuation of my previous essay, Always Understand People’s Intentions.

Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome, Charlie Munger says.

An incentive is something that motivates or encourages someone to do something. The most common incentive we think of is money. Who doesn’t want money? It’s universal because you can trade it for most goods in this world. Theoretically speaking, the right amount of money can buy almost anything. And the things money can’t buy are priceless.

Incentives can also be non-monetary such as meaningful work. Many people would take a pay cut to work at a high-moral company that is visibly improving society. Likewise, people would work a job that pays less but offers a favorable working environment, more time off, or flexible working arrangements.

Categories of incentives can be further bifurcated by their intrinsic or extrinsic nature. Intrinsic examples would be a sense of accomplishment, personal growth, and meaningful work, while extrinsic would be monetary, status, recognition, prizes, and bonuses.

If you want someone to do something, you must understand what they want, and find a way to give that to them in return. Everyone already knows this intuitively, but not everyone puts in the time and the work to explore this when they are trying to influence.

“Never, ever, think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives.”

Charlie Munger

Typically, people don’t have just one thing that will incentivize them. Sometimes it can be something you would’ve never guessed. If you invest the time to get to know the person, you can find what drives them, and then offer that in return for what you want.

Great leaders are masters at this. It’s how they’re able to recruit the best talent, retain them, and motivate them to excel. This should not be seen as manipulation, but more like a fair transaction. A fair but tricky one.

Imagine during this transaction, you need to communicate each other’s price in different currencies, without speaking the same language. That is sometimes what it is like to negotiate a deal by discovering and then offering appropriate incentives.

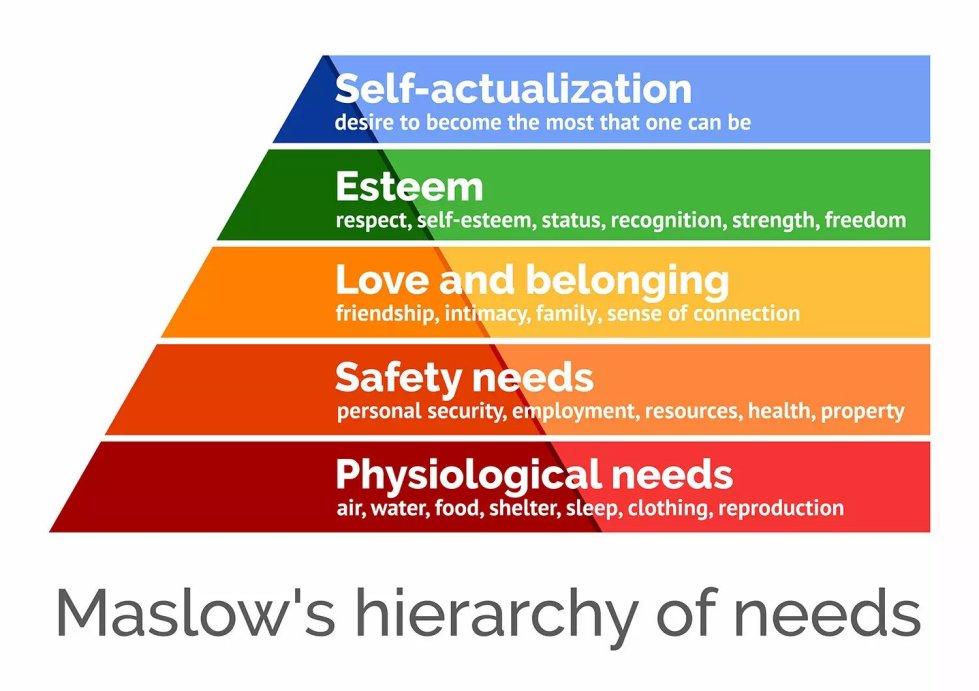

A good foundation to have is to understand the basic human drivers, such as Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. These are fundamental and universal needs found in all human beings that can be tied in with the more personal drivers of each individual.

A limitation to incentives is the nature of finite resources. No entity, regardless of size, has unlimited resources. Strategy, therefore, is about making choices on how we will concentrate our limited resources to achieve competitive advantage. All else follows from there.

The key to using incentives effectively is to make sure that they are:

- Valuable: The incentive should be something that the person values.

- Appropriate: The incentive should be appropriate for the task that you are trying to get the person to do.

- Timely: The incentive should be given as soon as possible after or sometimes even before the person has completed the task.

They should also be:

- Clearly communicated. People need to know exactly what they are being rewarded for and how they can earn the reward.

- Fair. People should feel like they are being rewarded fairly for their efforts.

- Sustainable. You don’t want to have to keep increasing the incentive in order to keep people motivated.

This information is relevant in any negotiation situation. This can be in business, or in a relationship, it can be monetary or non-monetary related. It applies to a high-stakes hostage negotiation, and also a trivial negotiation with a family member over who’s going to do the dishes.

Incentives drive the world. If you want to influence, learn its significance and how to use it.

“Incentives are the architecture of choice.”

Richard Thaler, Nobel Prize-winning economist