A blueprint for learning. I wrote this in parallel with Side Doors; an essay on gaining an intellectual advantage.

Humans aren’t particularly good at learning directly from facts. If we were, there would be no need for stories, allegories, and analogies which are commonly used in the most popular teaching methods such as books and school lessons.

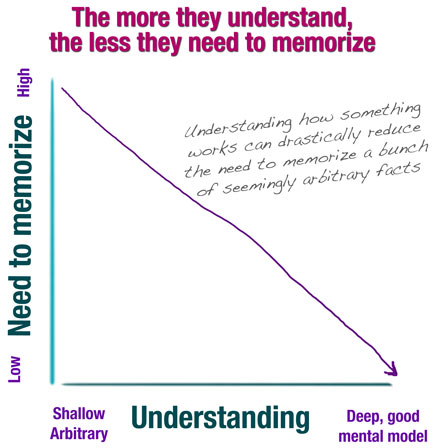

You can memorize or know something in theory, but to understand it is a different story. It’s one thing to memorize names, locations, dates, and concepts. But if you don’t understand it, then the information isn’t very useful.

This is because when you understand something, then you’re able to make connections, distinctions, and progress in the complexity of the subject. Meanwhile, memorization is static and non-compounding. Memorization is the ability to recite things. Understanding is the ability to mix intellectual ingredients to form a new concoction; a thought, idea, or pattern. Only then does it become useful knowledge[3].

It’s useful because you can be presented with a novel situation or problem and use your knowledge to solve the problem or capitalize on the situation. Contrarily, if you were just working with memorization, then you wouldn’t know how to apply that knowledge peripherally to other domains.

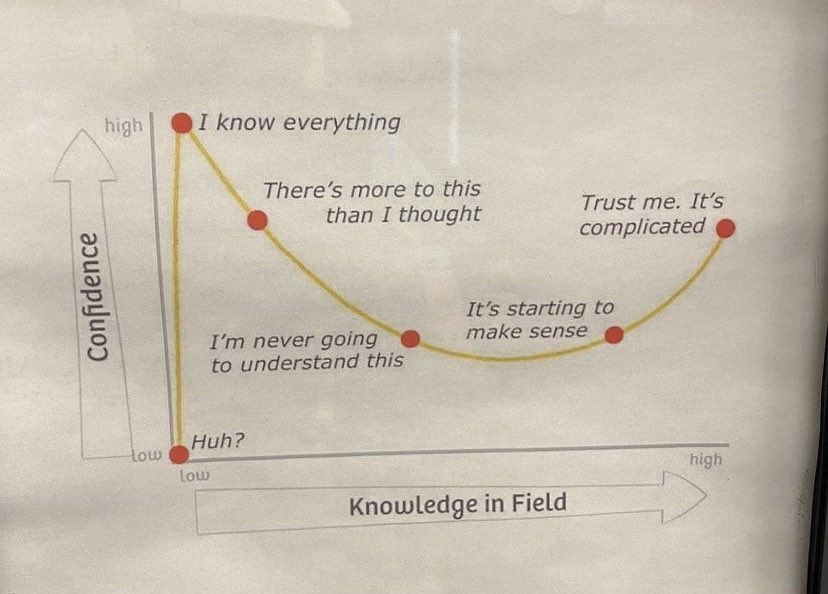

Understanding something can sometimes be a tricky task. If it were easy, we’d all be rocket scientists or quantum physicists. But it also isn’t as impossible as it may seem to reach a high level of understanding in a complex field.

It may seem impossible to the novice because the knowledge gap is initially so large. We’re on the ground floor looking to the top of a giant skyscraper thinking “How in the world do I get to the top of the building? Where do I even start? This is an impossible task.” But when you take the time to explore each floor of the building and work your way up step by step – gradually building your understanding, then it begins to feel very possible. There are no shortcuts to understanding. It takes time and effort.

Sure, genetic variation and environment play a role in mental dexterity. But this does not change the blueprint for understanding. There’s a method that can help improve the process for anyone.

You can probably remember a concept you once struggled to understand despite hearing it explained a bunch of times. And it’s not until you hear a new explanation in a certain or relatable way that it finally clicks.

There are no shortcuts. If you’re struggling to grasp something, then you’re missing one of two things. Either some rudimentary information, or you need a new perspective through different explanations. And since it’s not always practical for a book or lesson to jump back and forth between advanced info and fundamentals, they instead rely on “different explanations” through redundancy.

Let’s focus on books as an example. Books have arguably been the most valuable source of learning for the human species. It has been the most effective method of preservation and transmission of knowledge for over two millennia. Part of what makes books so effective is their redundancy. On average, books are 300+ pages long, and 10 pages each chapter prolonging a couple of key points that could’ve technically been summarized in a paragraph. Why do we spend so much time reading peripheral text just to grasp one idea that could be conveyed in a sentence?

The first answer to that question is more obvious: stories are quite enjoyable. And books—even non-fiction, often share stories to help explain ideas. When you enjoy what you’re learning, you grasp and retain information better. Secondly, perspectives or simply different ways of explaining are what make a concept or idea click. And good books are good at attacking principles from different angles.

Say we want to learn about the relevant topic of happiness. You know what happiness is, but you may struggle to apply it in your own life. So, you hire a life coach or talk to friends and family who give you advice. They all pretty much share the same basis, but it still doesn’t quite click. So, you continue to search for how to attain happiness. Then, during a random conversation with an elderly stranger, they tell you their life story and all the trials and tribulations they experienced through their journey of life. The story’s morale, though familiar in principle to everything else you’ve already heard, resonated deeply through the relatable adventures of its characters. It’s so simple, it suddenly makes perfect sense!

A common source of happiness is religion. This stems from the nature of aligning oneself with a greater good, emphasizing inner peace, relationships, community, gratitude, hope, and transcendence. These teachings become a fact to the preacher through powerful belief and redundancy. Religion doesn’t teach happiness as a factual instruction—do this to be happy. Rather, it’s taught through multiple facets in the gospel, rituals, traditions, stories, and the bible.

All it takes is one unique way of explaining the exact same thing—one new perspective, and then it clicks and becomes useful knowledge. And the way to maximize the chance of that happening is through redundancy.

To further simplify this phenomenon, I’ll use the redundancy technique to explain the redundancy technique.

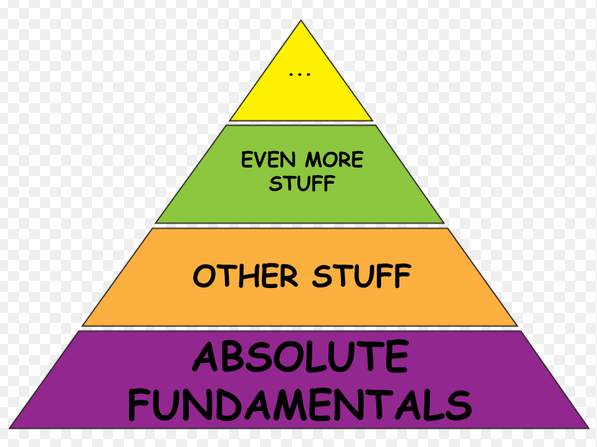

All learning, no matter how advanced or complex, is simply building blocks. If you’re struggling to comprehend something, then you need to take a step back; You’re missing a prerequisite.

Visualize learning as a semantic tree.

If you don’t understand that the number 1 represents (one) item, then you can’t truly understand addition or subtraction. You may memorize that 1+1=2, but you don’t understand why or what that means. Let’s say you do understand numbers but can’t yet solve 1+1. Then how are you supposed to understand and solve 1342 + 48 = 1390, let alone 12.641 + 397864.03 = 397876.671?

Another example is if humans didn’t understand aerodynamics, and birds or flying insects didn’t exist to give us biomimetic inspiration, then we would not know that planes need wings for lift and steer, and we may not have ever invented flying.

Neuroscientist and researcher Daniel Bor gives a lucid explanation of this idea:

“The process of combining more primitive pieces of information to create something more meaningful is a crucial aspect both of learning and of consciousness and is one of the defining features of human experience. Once we have reached adulthood, we have decades of intensive learning behind us, where the discovery of thousands of useful combinations of features, as well as combinations of combinations and so on, has collectively generated an amazingly rich, hierarchical model of the world. Inside us is also written a multitude of mini strategies about how to direct our attention in order to maximize further learning. We can allow our attention to roam anywhere around us and glean interesting new clues about any facet of our local environment, to compare and potentially add to our extensive internal model.”

Steve Jobs famously took this concept a step further by claiming that everything is a remix. I tend to agree. Herein lies the proof: Try to think of something, anything that is 100% abstract or unknown…

You can’t. It’s not possible. Even the most abstract or novel ideas derive context from something that is already known. AI, nuclear reactor, particle accelerator. These are all technologies beyond most of our scope of comprehension. Very sci-fi-like. But just like how a wheel must be invented before a car, and fire must be discovered before an internal combustion engine, even the most far-fetched technologies today have been built brick by brick. And the experts in those fields grew to understand them step by step.

And how about this for a change of perspective: Everything on Earth, everything ever observed with all of our instruments, all normal matter – adds up to less than 5% of the universe! The other 95%? Roughly 68% of the universe is dark energy, and around 27% is dark matter, both of which we don’t really know much about. And that’s just stuff we know that we don’t know. There is infinite knowledge that we don’t know that we don’t know.

I digress.

The point is, a leaf can’t exist without a branch. And the more branches there are (fundamental understandings) whether individually (in your brain) or collectively (as a species), the more leaves (deeper understanding) there will be. And this is why “everything is a remix.”

To tie that back to the main point, which I could’ve simply stated in a single sentence; Elaboration or digression through stories, allegories, and analogies are what made this idea a lot more useful to you. It’s what allows the idea to stick and make a lot more sense. And if the idea still doesn’t resonate with you, then you just need to hear it explained differently—redundancy!

I could’ve written this essay in a couple of sentences stating the facts. I could’ve provided research that explains the roles of neurons, synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and the interconnectedness of brain regions that conclude the same theory. But instead, I gave you a couple analogies and a different perspective.

With that, you now understand how to learn and teach more effectively. The knowledge has become useful to you thanks to redundancy.

[1] Redundancy is also good for forming new/unique insights about the same topic. Like when you re-read a book for the second or third time and take away things that you didn’t the first time around. Or being able to put two somewhat unrelated pieces of knowledge together to form a new idea or conclusion.

[2] Redundancy is also important for building trust with the reader. If I simply state a “fact” without explaining how that was concluded and you knew nothing about the author (me), then how would you know that it’s accurate or true? Redundancy allows me to explain why it is true.

[3] Knowledge compounds: I sometimes find it impossible to articulate why I’m so confident about an investment or business decision. Probably because there’s never one reason. Rather, it’s a combination of historical insights, personal experience, pieces of knowledge from books, interviews, podcasts, lessons, etc. A mixture of information on top of a cognitive filter that I learned to weed out biased and poor-quality information. Also, importantly, the info itself wouldn’t be useful without the temperament I developed (somewhat contrarian, long-term outlook, stoic, open-minded). These are all things I learned along the way and have become ingredients to create new insights, thoughts, and ideas. A sort of tacit knowledge, or what’s known as intuition. Just like mixing hundreds of unnamed chemicals into a solvent, the resulting solution, as you can imagine, would be very difficult to accurately explain how it resulted as such.