Understanding why stock prices move, and how to beat the market without outsmarting anyone.

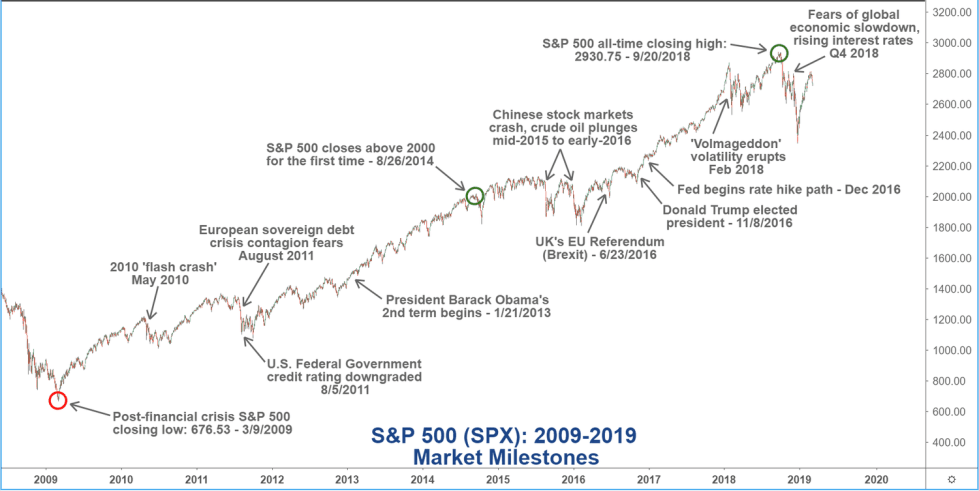

The price of any asset over a period of time has a zigzagged line. No matter if it gains 1000%, loses 1000%, or ends the year flat, it will move up and it will move down. This is almost as certain as the laws of physics.

Fun fact, one of the strongest early indications revealing that Bernie Madoff was a fraud was the fact that his returns did not follow this financial law of zigzag over time.

Harry Markopolos was one of the first people to uncover the ponzi scheme. In his book, No One Would Listen he recalls one of the early moments of his discovery “Pointing to the 6 percent correlation and the 45-degree return line, he said, “That doesn’t look like it came from a finance distribution. We don’t have those kinds of charts in finance.” I was right, he agreed. Madoff’s strategy description claimed his returns were market-driven, yet his correlation coefficient was only 6 percent to the market and his performance line certainly wasn’t coming from the stock market. Volatility is a natural part of the market. It moves up and down—and does it every day. Any graphic representation of the market has to reflect that. Yet Madoff’s 45-degree rise represented a market without that volatility. It wasn’t possible.”

A ton of money is lost and made during these moments of zigzag, also known as volatility. So it can be very lucrative to understand why it happens and perhaps be able to adequately predict how it will happen.

Side note: As of today, it’s simply not possible to predict the market with perfect accuracy. And this truth becomes more evident the shorter your investment time horizon. Millions of algorithms have been developed and tried by some of the smartest mathematicians in the world (finance draws many of the smartest people in the world due to its pay) and none have succeeded. So if you plan on developing a breakthrough, just know you’ll need something as profound as a time machine. Arguably not completely impossible, but good luck.

The proof that no government or person holds the key to this tool is that we would’ve already had the world’s first trillionaire and we would’ve seen someone breaking the financial law of zigzag. There is nobody in the world today who can reap the upside in the market without occasional downside. Also, the large players in the finance industry are willing to pay massive sums in the millions of dollars a year to a person who can provide a marginal advantage. We’re talking about a 1% competitive advantage with minimal downside risk.

So let’s get to the main topic of discussion, what causes zigzag in the market and is it predictable? Here are a few of the main market forces and why they happen:

1. Institutional Investors generally aren’t looking for huge 100%+/yr returns. They’re dealing with large amounts of money, so they have a lot to lose. As a rule of thumb, the larger the sum of capital, the lower the desired return because the risk tolerance is lower. They also gain a lot more per percentage gained than a small portfolio; a 5% return of $10 million is $500,000 vs a 5% return of $10,000 is only $500. They want to beat the market but with relatively low risk.

Because they often use other people’s money, if they don’t perform well consistently, then people will go elsewhere to a better fund or investment. It’s highly competitive. Because of this, their time horizon must be relatively short at 1-3 years. They can’t afford to hold through a market downturn or a recession. This means they try to sell to avoid even a temporary loss and buy to reap even short-term returns as long as it makes sense considering taxes. However, they don’t act immediately because their investments must be backed by research, planning, and bureaucracy.

Their decisions are typically more fundamental and analytically driven; projected earnings, competition, industry growth, economic conditions, production costs, management, etc.

According to a 2021 study by Morgan Stanley, institutional investors account for ~90% of the daily trading volume on the Russell 3000 index, which is the broadest major U.S. stock index. Because they control such a large portion of all U.S. financial assets, institutional investors have considerable influence over the markets for most asset classes.

This is a large reason why, if you have a long enough time horizon, you could certainly outperform the market even as a layman. The reason most investors are unable to do this is because 1) it’s not always straightforward to choose a long-term winner, and 2) most people are simply too emotional and can’t hold when the market is down. When they see big losses on paper then they sell, even if the business is still strong, still has strong management, and still has endless potential. Successful investing is all about price dislocations.

Joel Greenblatt, an American academic, hedge fund manager, investor, and writer worth $30 billion has a free transcript of a class he taught on investing at Columbia University. You can find the full transcript here. One of the main points he makes is that regular investors can realistically outperform the market with a long-term time horizon. You just need to learn how to value a company, then buy when it’s cheap and hold it despite any short-term zigzag.

2. Traders often move on momentum. They may initiate a movement or feed off of the movement from institutional investors like a hyena scavenging the scraps. Different traders use a plethora of different strategies from chart analysis, trend following, mean reversion, and news trading. The time horizon can also greatly vary from algorithmic trading that executes trades in milliseconds, to day trading or long-term trading that lasts months or years.

Some trading strategies are sort of a pseudo-science compared to traditional or long-term investing as they can sometimes be speculative and rely on gut feeling. Nonetheless, some strategies can be systematic and very effective at earning outsized returns.

3. More recently, small Retail Investors have proven to overpower even the large and powerful institutional investors if they work cohesively (GME, AMC short squeezes). Assets with cultural influence can rally or tank simply because a bunch of individual retail investors get together to move the price. This price movement is usually artificial and ephemeral.

However, sometimes the cultural influence can be longer-lasting and form a sort of cultish following. For example, Tesla stock has a history of garnering large and sometimes unprecedented support from retail investors. Much of this is caused by the company’s fanbase and admiration for its founder, Elon Musk. Strangely, it has actually made the stock fairly robust due to the inflows during price drops from people “buying the dip”.

Generally, retail investors have a minor effect on the broad U.S. stock market with daily trading volume typically averaging less than 10%.

So how can we apply these market forces to our financial benefit? Below, we’ll explore a working example of how to beat the market without the need to outsmart anyone.

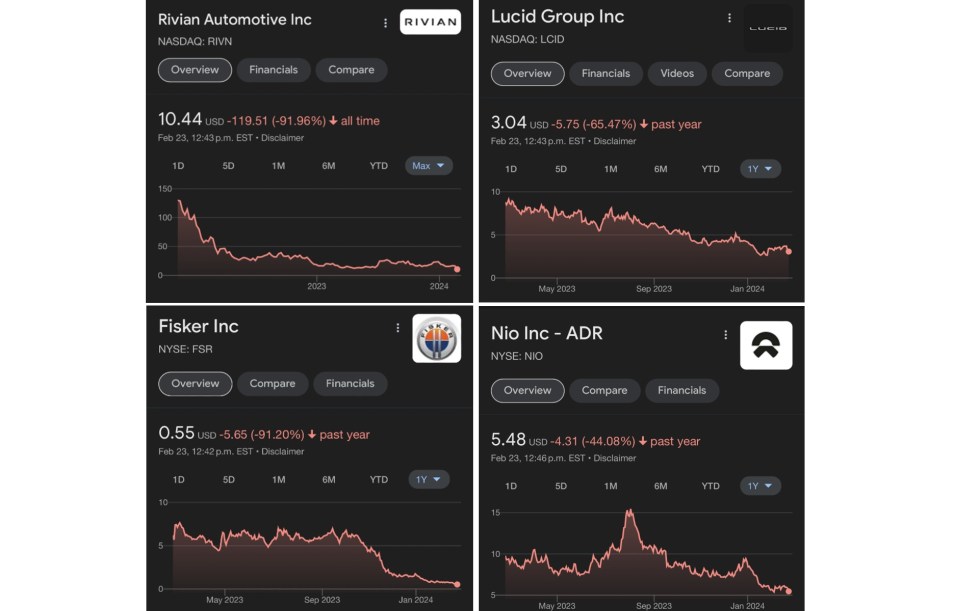

As of the beginning of 2024, EV market demand and growth have slowed significantly due to the macroeconomic state of affairs. China’s economy, which accounts for ~60% of EV sales worldwide and almost a quarter of Tesla’s revenue, is currently in a poor economic state and its citizens aren’t spending like they used to. As a result of all this, smaller inefficient EV startups will fail or take a big hit, legacy carmakers have rescinded their EV projects, lithium prices have plummeted >80%, EV margins are getting pinched, and the overall outlook for the industry is poor. As a result, the largest EV maker in the U.S., Tesla, is down big to start the year.

Looking back at the common market forces, 1) Institutional Investors sold Tesla shares knowing that in the short-term, the stock wouldn’t perform well as earnings would be down and the growth outlook has weakened. Tesla now also has potential survival risk depending on how long these economic pains last. 2) Traders add to the downward momentum by buying puts (betting that the stock will go down) or reallocating their money elsewhere. 3) Retail Investors, who represent a smaller portion of volume, might “buy the dip” but with the sentiment so poor, they’re inclined to hold off until an apparent bottom or even sell to fund a better-performing investment. Regardless, their impact will be relatively minimal.

This is where investors with a long-term time horizon come in. You don’t need any special knowledge or tools, and you don’t need to outsmart best-in-class financiers. You only need a long enough time horizon and conviction to stick to your strategy.

Despite the sell-off, Tesla still has a strong management team, competitive advantages, solid product, >50% EV market share, and the long-term outlook of the EV market and renewable energy is still very promising. If the current macroeconomic conditions weren’t tumultuous, the entire EV market would likely continue its upward trajectory, and Tesla being at the leading edge of the industry, would perform well. So I conclude that this is a good opportunity for me to buy TSLA at an attractive price due to a price dislocation. It’s not an esoteric conclusion either. It simply doesn’t fit the demands or strategy of other investors. This explains why there is a price-to-value dislocation given the timing.

Since nobody can time the market, and I’m unlikely to outsmart big finance, a good buy-in strategy is to dollar cost average into TSLA during this downturn since I don’t know how long these struggles will last.

As Warren Buffet puts it “If you are working with a small sum of money… and are willing to do the work, there is no question that you will find some things that promise very large returns compared to what we will be able to deliver with large sums of money.”

Tesla is just a single example. And again who knows, I may be wrong. I don’t have a time machine (or do I?). Notice, I didn’t elaborate on why they still have a competitive advantage in the industry or where I got my information from. This analysis is up to the individual investor to do your own due diligence.

If you see that the long-term outlook for a company and its position in a growing industry is promising despite short-term zigzag, you may have just found a solid investment as long as you have the time horizon and the balls to see it through.