My previous essay, 2 Types of Information, is a short preamble to this one.

Average is everywhere. It is, by definition, the best way to represent or relate to the most people in a single context. Similar to stereotypes and generalizations, there may be some truths to them. But they aren’t fully accurate. An average cannot accurately describe such a diverse group of data points.

Average spreads itself too thin trying to relate to everyone at once. This happens in all forms of average in many different domains in life: average advice, average information, average products and services, average statistics, and even average behaviors.

Advice

Naval Ravikant believes that the best way to use advice is to reject most of it. I highly recommend reading his short explanation about it here.

Essentially, he believes that “if you ask a successful person what worked for them, they often read out the exact set of things that worked for them, which might not apply to you. They’re just reading you their winning lottery ticket numbers… The best founders I know read and listen to everyone. But then they ignore everyone and make up their own mind.” Advice offers anecdotes to recall later, when you get your own experience.

Advice is either highly specific to what worked for one individual (just like Naval explained). It’s specific due to their peculiar combination of character traits, upbringing, strengths and weaknesses, etc. The polar opposite type of advice is so general, so average, that it applies a little bit to everyone and perfectly to no one.

Henry Ford had a totally different upbringing from Steve Jobs. Steve Jobs had a totally different leadership style from Abraham Lincoln. Abraham Lincoln had totally different tendencies from Elon Musk. They all probably agree on many things, but they also have a lot of conflicting advice.

Like their leaders, different businesses also operate on different sides of the average. Almost every successful company today was once a business operating in a way that contradicted the average advice. Todd Graves, founder of Raising Cane’s, first wrote his business plan in university and received a poor grade because his professor didn’t like the concept. He thought his menu wrongfully excluded healthy items, which would deter too many paying customers.

That professor was actually correct based on the precedents at the time. All successful restaurants were inclusive to different types of diners, broadening their customer base. Despite this, Todd’s contrarian opinion prevaled and he now has a wildly successful company, thanks almost entirely to his ignoring the average advice.

Facebook started as a platform for people to share personal information about their lives online. This was during a time when online anonymity was the norm, and people used pseudonyms to hide their identity on the web. Facebook’s entire existence contradicted the average advice of the time.

Even personal average advice can be flawed. I will really try to test the logic of my argument here with an extreme example. You’ve probably heard the advice to work hard, go to school, and don’t do drugs. On average, each of those is generally solid advice to follow. But there are still proven paths to success without obeying any of those three things.

When it comes to hard work, there’s also much truth to the saying work smarter, not harder. Many people living paycheck to paycheck work just as hard as your average self-made millionaire. How about Bill Gates “If you want to get a task done faster, give it to a lazy man, he’ll find an easier and faster means of doing it”. Or Abraham Lincoln, “If I only had an hour to chop down a tree, I would spend the first 45 minutes sharpening my axe.”

And don’t get me started on the advice about going to school. Countless successful people never completed college, and some not even high school. You’ve probably heard the saying that A students work for the B students, and the C students own the company. Again, it’s generally good advice to complete at least high school and maybe university, depending on your goals. But there are situations where higher formal education is not necessary at all.

Even the most outrageous example of the three, don’t do drugs, can be steelmanned. Many successful people run on the drug caffeine. Many regularly drink alcohol or consume tobacco. Some have even taken harder drugs without ruining their lives. Steve Jobs, though he doesn’t recommend it, called his LSD experience “one of the two or three most important things [he had] done in [his] life,” and joked that Bill Gates would have had “more taste” in his product design if he had “dropped acid”.

I personally resonate with Mark Zuckerberg’s philosophy of “raw dogging reality,” where he prefers not take any drugs at all. Not even caffeine or Tylenol unless absolutely necessary. Again, just average advice, trying to tailor to everyone at once. As a result, its effectiveness gets diluted.

I have studied literally countless real-life success stories. I’ve studied enough of them to know that if I study any more, I am being counterproductive to my success. Instead, I should act on the information I have now if I want results from that work. But I still do it anyway, it’s a weird enjoyment of mine.

Through studying these success stories, I’ve found that though they all share common themes, their paths and strategies all differ. Sometimes they differ pretty significantly. And I am not exaggerating when I say many of them have conflicting advice.

Patrick O’Shaughnessy says he works better without setting any goals at all. Probably most others would insist that you set highly specific goals and update them regularly. Some advise that you work on what you love and let money follow. Others advise you to work wherever it pays best, then do what you love outside of work. Some insist you carefully control all aspects of your business, while others urge you to delegate and only work on higher managerial tasks.

The only right answer is to listen to all advice, so you know your options, then use only what applies to your situation.

Another great example is from a podcast episode with David Senra of Founders and David & Ben from Acquired. Both are highly respected in the business world. They argued,

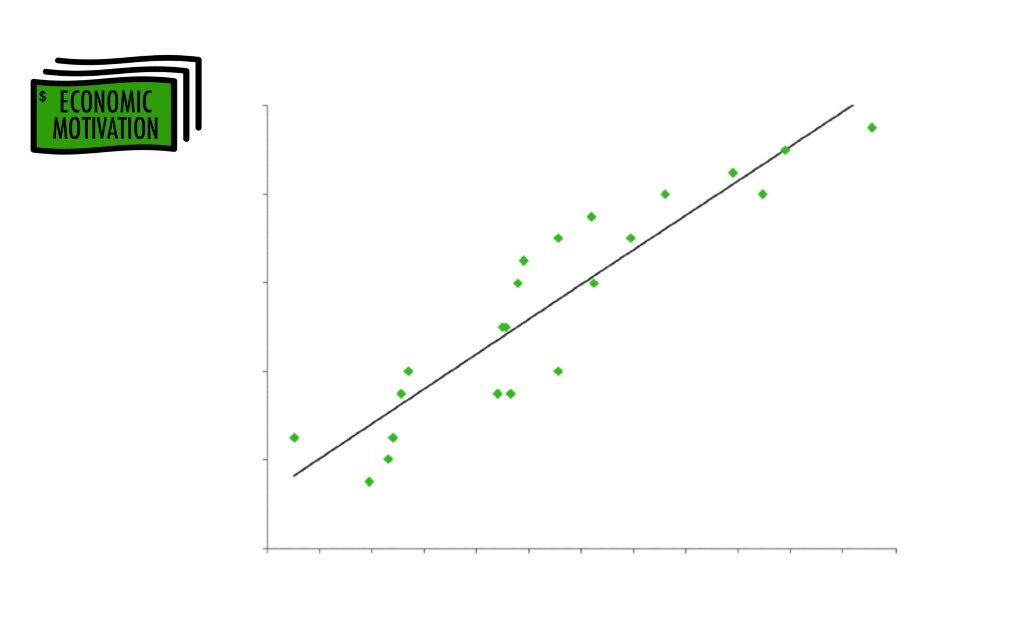

“if someone’s going to advise you on starting a podcast, they would say, do a 30 to 40 minute episode and do it weekly so you release it at the same time, have a guest, so that way that person promotes it too. And we’re like, okay, well, we do the opposite of all of those things… The conclusion I’ve come to is advice is an average and reality is a distribution. And averages suck because they hide the distribution. You kind of want to know the shape of the distribution, and you kind of want to know things that apply to your specific data point, not like the average thing. And I think advice is always an average that hides the distribution. And if you know that you’re actually an outlier in some way, then you have to sort of selectively follow advice because it may not apply to you.”

To use advice effectively, you must first understand that most advice you hear is average. That doesn’t make average advice bad. But since it’s tailored to everyone, it naturally won’t fit anyone perfectly. That’s precisely what average is.

Secondly, take in all advice but only use what works specifically for you.

Products and Services

This one is easier to explain. A bespoke product is custom-built, meticulously crafted to one client’s likes and needs. The problem with bespoke products is that they’re not economical and thus usually impractical to produce at scale.

The vast majority of successful businesses produce repeatable products. These mass-produced products have infrastructure built around them to where they can be made affordably, fixed easily, modified, and troubleshooted. For example, take a Toyota Corolla vs a Koenigsegg CCXR Trevita. Both are cars. One is mass-produced, and the other only has two made in the entire world.

The Corolla can be repaired by any semi-competent mechanic in the world. Replacement parts can be sourced easily, troubleshooting information can be easily found online, and customizations can be DIY’d by anyone. The Koenigsegg, on the other hand, can only be maintained or repaired by a handful of specialists in the world. A simple oil change could cost more than a college tuition. The cost of development for that car alone could buy everyone in your family one Corolla each.

All businesses are fundamentally motivated by profit. To earn a profit, you typically need to sell a high quantity of a product. In order to sell a lot of a product, you must achieve volume production. In other words, you need a way to easily reproduce your unique value.

For example, go into any McDonald’s in the world, and they all have the same Quarter Pounder burger on any day of the year. Another example, your 2025 Honda Civic is exactly the same as your neighbor’s 2025 Honda Civic. They were built using the same type of machines and the same supply chain techniques.

The opposite of this, a bespoke product, is like creating a whole new business all over again for a one-time fee and no recurring revenue. Creating one business is hard enough. You have to develop the product, establish relationships with customers and suppliers, refine its supply chain, conduct marketing, and sales. With a bespoke product, you’re essentially doing that all over again each time you create and deliver a new product/service. It just makes no sense, it’s not economically feasible, and it is less impactful.

So how does this apply to average?

The typical business has an average solution. It must be average because it needs to please many different types of people with only one product.

The iPhone is an average product. Everyone has different specific preferences and needs for a smartphone. I cannot choose the exact color and size of my iPhone; I can only choose the limited options that Apple offers.

They offer a small variety because it must be economical to reproduce. If they had 100 different colors to choose from, that would take a ton away from their profit. Same with size and other customizations.

As of mid-2025, Apple has sold over 3 billion iPhones worldwide, so people undeniably love the product. But it still fits noone perfectly. This is why most businesses are a one-size-fits-all.

We may have good and even great products, but seldom a perfect product. Average is, unfortunately, a necessity in business.

Information

(Read my essay, Two Types of Information)

This is another important one to understand because the quality of your research depends on it. Information can also be average. If information finds you, then it’s most likely a topic du jour. Hearing it from a friend, discovering it on social media, or a news algorithm feeding it to your page are all examples of information finding you.

If the information is popular, then it must have enticed a lot of people. It must’ve been noteworthy, provoking, emotionally charged, or just very interesting. And the issue with that is oftentimes the truth is boring and/or nuanced.

Do you remember the drone hysteria in the USA a few months ago? How about the devastating plane crashes that happened in 2025? Every news site and blog in the world was sharing its strong opinions before any sufficient investigations were completed. Fast forward a few months to today, and most of the world already moved on, not caring to reflect on the new information.

The truth of both of those occurrences was nuanced and much more benign than the news made it out to be. Commercial planes are still the safest mode of transport and are getting safer, and we are not being attacked by UFOs or mysterious drones.

Be wary of average information and the track record of their sources. Expect the truth to have more nuance, less excitement, and potentially less certainty of the answer.

Average provides a glimpse, but never the full picture. Accuracy lives at the edges, far beyond the safety of the mean.